The Pursuit of Prayerfulness & Selflessness: Father James Martin and Richard Lui

Narrator: Welcome to the Jesus Calling Podcast. As we seek to live a life where we can be a light to others, with a heart of prayer to lift their needs over our own, it helps to remember the guidance given in the Bible from Philippians 2:3–4, which says, “In humility, be moved to treat one another as more important than yourself.” It’s in prayer and in selfless service that we can model the life Jesus lived by example in “loving others as much as we love ourselves.” In this episode, we explore how to begin to pursue a life of prayerfulness with basics on prayer from Father James Martin and also hear from MSNBC and NBC news anchor Richard Lui about how he learned about what selflessness really means as he cares for his father who has Alzheimer’s disease.

Father James Martin is a Jesuit priest, an editor-at-large at America Magazine, and the author of Learning to Pray: A Guide for Everyone. Father Martin believes that prayer is for everyone, and encourages those who might not have prayed before, or perhaps are intimidated by the thought of it, or even think they’re “not doing it right,” by reminding them that prayer is for everyone and that God is lovingly waiting to hear from us and desires that interaction. Father Martin explains what prayer is, how to start praying, and how a daily prayer practice can transform our lives.

Father Martin: My name is Father Jim Martin, I’m a Jesuit priest, editor-at-large of American Media, and author of a couple of different books, including most recently Learning to Pray: A Guide for Everyone.

Early Years of Faith

I grew up outside of Philadelphia in a suburb called Plymouth Meeting. I was raised Catholic, but wasn’t super Catholic. My parents were good people, but—I would say and—we didn’t seem to favor the kind of practices that a lot of devout Catholics and Christians do. So we went to mass, I’d say, most Sundays. We said grace maybe, oh, Thanksgiving, Easter, and Christmas.

I didn’t go to a Catholic high school. I ended up going to the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, where I studied finance. We used to joke “it’s fi-nance and not fi-nance” because you can get more money if you say you studied fi-nance, it sounds a little more sophisticated. I took a job with General Electric in New York City, which was very exciting. But then gradually I just sort of realized it wasn’t for me. Business is a real vocation for a lot of people, but I felt like the square peg in a round hole.

And then one night I came home and turned on the TV and saw a documentary about a Trappist monk and writer called Thomas Merton. And that prompted me to read his book, The Seven Storey Mountain, and that got me thinking about doing something else. And I entered the Jesuits, which is a Catholic religious order, at age twenty-seven.

So really, my image of God was the image that a lot of Christians have—and I’m not faulting them, this is how I felt—that God was kind of out there and would dispense favors to me if I did the right thing. And so in the Jesuits, I was invited to think about having a personal relationship with Jesus and a real, open relationship with God.

“I was invited to think about having a personal relationship with Jesus and a real, open relationship with God.” – Father James Martin, S.J., on entering the Jesuit order

How to Pray: With Honesty, Trust, and Acceptance

I think most children have experiences of God, but they’re not encouraged to think about them as such. So I talk about three ways of praying when I was young. One was a petitioner’s prayer, which is fine. I still do it, right? I did it this morning for something. I need some help, God. But that’s kind of one way, right? I mean, it’s, Please help me, which is fine. Again, I would ask for things when I was little. I would ask for a puppy or to do well on my math test.

Then the second way of praying was sort of talking to God, trying to essentially convince God of why I deserve something. A little more conversation, still kind of one way. The idea of a sort of relationship or conversation really didn’t enter my consciousness until the Jesuits.

One of my favorite models for prayer was pointed out by a Jesuit theologian named Karl Rahner, a German Jesuit. I think this is brilliant. This really changed, I would say, not only my way of praying but how I understood prayer. And he said that the perfect model pray-er, the one who prays, is, of course, a big surprise—Jesus. And he says that Jesus’ prayer is characterized by three things. This really blew me away when I first heard it. First, honesty. And he points to Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane who says, “Lord, let this cup pass Me by.” He’s being honest, right? I mean, at that moment, He’s saying, “I don’t want to suffer.” So He’s being honest.

Second, trust. And he points to the phrase from the raising of Lazarus in John 11, where Jesus says in front of the crowd, as you remember, “God, I know that You hear Me,” so trust.

And third, acceptance. And he goes back to the Garden of Gethsemane, and he looks at that line, “Yet not My will, but Your will be done.” I have found that so helpful because, you know, I think that a lot of us skip one or the other steps. A lot of people say, “Well, you can’t be honest in prayer because, you know, you should be happy or you shouldn’t be complaining or you shouldn’t ask for something.” And then the trust, a lot of people skip, right? It’s sort of like, I’m throwing my prayer out there, and I’ll just hope it comes true. And then the acceptance is something that a lot of people skip. So I found that super helpful: honesty, trust, and acceptance.

How to Know When You’re Connecting with God

So let’s say you’re in a difficult situation in life, and you’re praying over a scripture reading. Let’s say it’s the storm at sea. Right? And Jesus is calming a storm. And you find yourself really drawn to the image of Jesus stilling the storm, and you relate it to your own situation. You feel in your prayer this great sense of calm. You feel calm. You feel encouraged. You feel hopeful. You feel inspired.

Now, if you were to say to me, “Where’s that coming from?” I would say, “Well, you know, that makes sense with what we know about God.” Right? I mean, Jesus says, “Fear not.” Jesus stills the storm. God would want you to have a sense of calm that seems to lead to a growth in charity and love and hope in your life. So, I mean, you really would have to make an argument that that’s not coming from God. And so part of it is, you know, it is testing it out.

But for the most part, I think that people can trust within reason the kinds of things that happen to them in their prayer and in their daily life. If they feel that it is God’s presence, it usually is. So I think the thing is really encouraging people to trust more than they do that this is God reaching out to them. In the Jesuits, we have an expression: “The Creator deals directly with the creature.” So it’s encouraging people to trust themselves and trust what’s going on as authentic.

It’s like any good friendship. If, let’s say—God forbid—someone who’s close to you died in your family, and we see each other, you know, for dinner a couple weeks later. Now I’m going to want to know how you’re doing. I’m not going to say, “But I know she’s sad so why do I need to say anything?” And you’re not going to say, “Oh, well, he knows I’m sad, so I’m not going to share anything.” No, I mean, friends want to know each other. And God wants to sort of enter into this deeper intimacy with us, and I think the invitation even more is for us to enter into deeper intimacy with our Creator.

“For the most part, I think that people can trust, within reason, the kinds of things that happen to them in their prayer and in their daily life. If they feel that it is God’s presence, it usually is.” – Father James Martin, S.J.

One of the most fruitful ways of understanding is prayer as a personal relationship, and all the things that make for a good personal relationship make for a good relationship with God. Now, obviously, our friends are not the same as God. But the idea is that He says if you can look at the categories that make for a good friendship, it can help you and your prayer.

So what do I mean by that? I mean, if your relationship to a friend is only obligation, right, then what kind of a friendship will that be? Right? Well, eventually it might get a little cool and you might even start to feel a little resentful of the friend. Now, that doesn’t mean that we don’t have responsibilities to our friends. Right? I mean, to care for them and help them and listen to them and sometimes provide for them if they’re struggling. But it does mean that it is more than just an obligation. And the same for prayer, I would say. I would say we do have an obligation to pray. But that’s not it. That’s not the sum total of what your prayer is.

“All the things that make for a good personal relationship make for a good relationship with God.” – Father James Martin, S.J.

You know, any good friendship requires time. Let’s say I were to ask you, “Who is the most important person in your life?” And you say, “Oh, my best friend from college.” And I would say, “Well, how much time do you spend with her on the phone catching up every year?” And you say, “None.” I’d say, like, “Well, what kind of a friendship is that and how important really is that person?” So that’s what I’m saying, that any good relationship requires some time. So I see it less as an obligation and more as a kind of requirement for keeping up a good relationship.

Prayer Is for Everybody

People think prayer is kind of an aptitude. I’m trying to think of something, you know, I can sing. Right? I have a good voice. And if you don’t have a good voice and you don’t have, you know, sort of an ear for music, that’s it. Right? So give up. So people think, Well, I tried it and I guess I can’t do it. Or like playing, skating or dancing or something like that, or painting and that’s it. And they give up, which is sad because prayer is for everybody and because God is for everybody.

Everyone I’ve ever met goes through dry patches. And look, sometimes I sit down in my chair every morning and not a whole lot feels like it’s happening. Something’s happening on a deep level. I think we have to trust that. But that’s okay, that doesn’t mean I’ve done something wrong or that God is mad at me. That’s not the way God works. It’s just, you know, it’s just kind of the ups and downs of the spiritual life. And so that can make people feel suspicious of prayer as well, that, I’ve done something wrong and God’s not going to be with me. And so all these things need to be challenged.

So many people have an image of God that they have from their childhood that can be really burdensome and really unhelpful and actually not God. So one of my friends memorably described God as, which I love, “the parole officer.” First of all, we’re evil and we’ve just gotten out of jail, and God’s looking for something that we’ve done to kind of condemn us and to send us right back to jail. Well, again, obviously, God wants us to lead good lives and act lovingly and do the right thing. But that’s not the God that you find in Jesus Christ. You know, this is the God of compassion and mercy and forgiveness.

And often what I try to do is I try to say, “Now, look, there’s the God that you have in your mind that may be a burden to you and then there’s your actual experience of God.” Trust that experience. And then that can be really helpful for people to get rid of some of the unhelpful ideas and constructs of who God is. When someone has an experience of God, either in their daily life or in their prayer, that’s really unmistakable. Right? They feel God’s presence. They feel that God has reached out to them in a particular way. And by that I mean something that happens in prayer, emotion, insight, desire, memory, feeling something, connection—as well as in their daily life—which could be just a kind word or just an insight or a feeling of God’s presence. And when you can invite that person to see that this is God communicating with them and that it is a sign of God’s love for them, it can be overwhelming. You know, it’s like, “Who, me?”

God loves us. And so once people are able to accept that love, it really is transformational. They know that they’re valued in who they are and that they are enough.

“God loves us. And so once people are able to accept that love, it really is transformational. They know that they’re valued in who they are and that they are enough.” – Father James Martin, S.J.

I’d really encourage people who feel that they’ve never had a satisfying prayer experience, that they can’t pray, that only their prayer is dry, that they’re not praying the way they “should pray” or that somehow their prayer is unsatisfying—I’d encourage them to keep at it. The idea is to trust that God is waiting to hear from you and that also there’s no wrong way or right way to pray. Right? Anything that helps you to feel closer to God is something that you should try to do. And so just be open to that and to allow yourself to let God reveal Himself to you in the way that God wants to reveal Himself to you, not to someone else, and to just keep trying because really prayer is available and is open to everyone. If I can pray, you can pray.

“The idea is to trust that God is waiting to hear from you and that also there’s no wrong way or right way to pray.” – Fames James Martin, S.J.

Narrator: Father Martin’s book, Learning to Pray: A Guide for Everyone, is available everywhere books are sold.

Stay tuned to Richard Lui’s story of a selfless choice to press pause on his news career while caring for his elderly father, right after this.

Jesus Calling®: The Story of Easter from bestselling author Sarah Young uses vibrant illustrations, storytelling from throughout the Bible, and short Jesus Calling® devotions to show how Easter was part of God’s plan from the very beginning. Available in both a picture book and board book format, Jesus Calling: The Story of Easter can be found wherever books are sold.

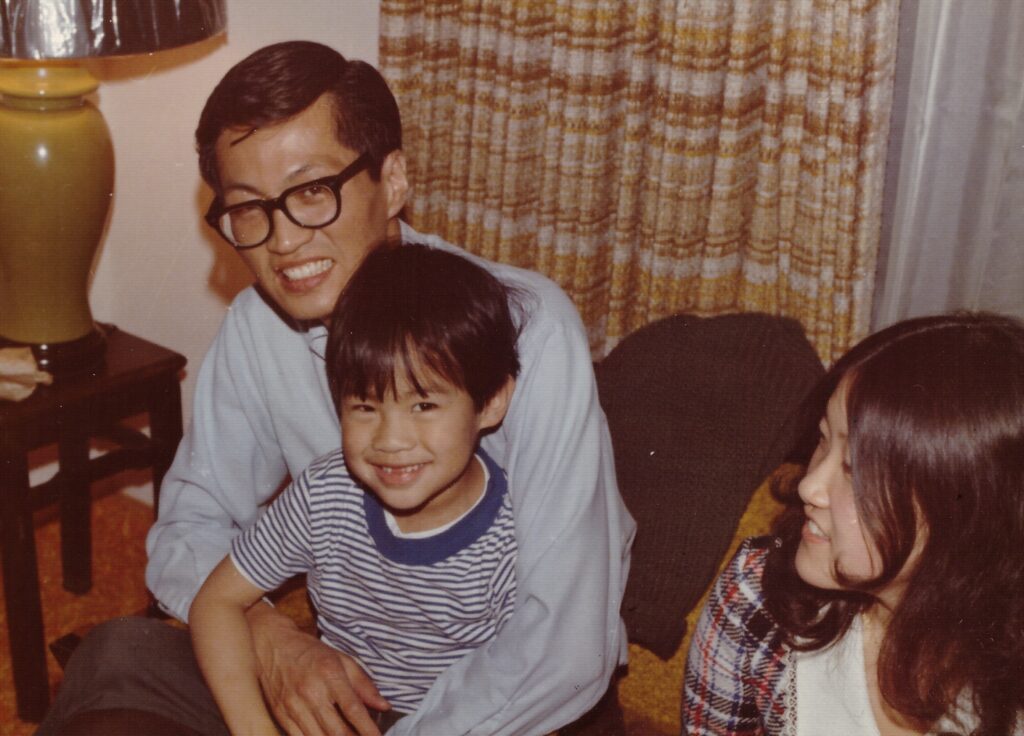

Narrator: Richard Lui has been in the world of television, film, technology, and business for over thirty years as an anchor at MSNBC and previously with CNN Worldwide. He is the first Asian American to anchor a daily national cable news program, and he is a team Emmy and Peabody winner. Geared toward success, Richard had always tried to model the example his father, a pastor, had demonstrated toward his family—one of selfless sacrifice. This was put to the test when Richard and his family got the news that their father had Alzheimer’s Disease. Richard made the tough decision to take time away from his growing career and choose a selfless path to help care for his father. The choice presented challenges and struggles, and Richard wanted to explore why the path of selflessness can be difficult. He writes about his journey in his new book Enough About Me: The Unexpected Power of Selflessness, and shares in this episode how even small choices toward selflessness lead to a more fulfilling life.

Richard Lui: Hi, my name is Richard Lui. I’m a journalist and anchor over at NBC News and MSNBC, and I am also a caregiver for my father who lives in California. I live in New York and typically fly back to take care of him two to three times a month.

Looking Up to Your Father

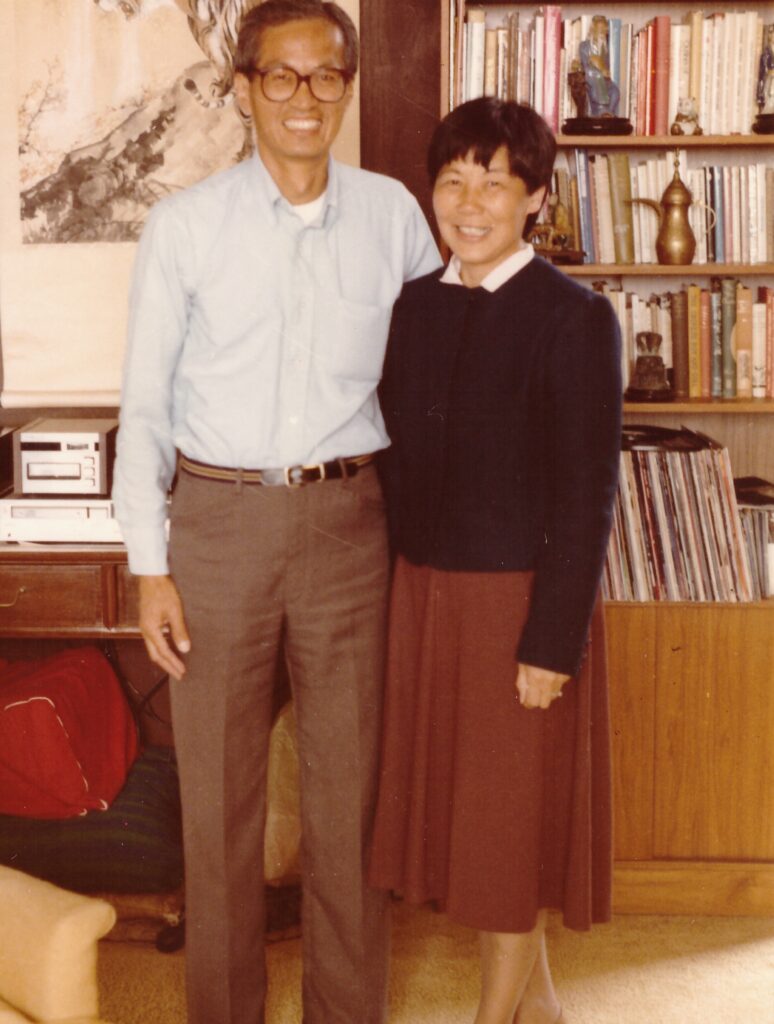

Dad was a pastor. And as a young kid he, as a youth pastor, wanted us all to go to church. And his influence, I think, early on we were kind of unsure. There’s four of us, four children, and for me going to church every weekend and during the week meant that for me, I had to be basically one of the apostles—that’s what I sort of joke about right now. But that influence of my father was, I think, imprinted on me pretty early. My mother, also being a choir singer since she was, I think, the only one in her family. She was born in China, came over when she was two, grew up in L.A.

My dad was born in San Francisco, Chinatown, no hospitals at that time. And the Cumberland Presbytery, led by a group of women who are missionaries from Texas, had started a church up the block, and he would climb up the block from Chinatown to go to church. And he knew no other church for the rest of his life. Cumberland Presbytery would be the place he would travel to every single year for the presbytery meetings.

I know being a pastor [was] just different in general because it’s not like the majority of Americans are pastors. Number two, him being a person of color, being a pastor, you know, in the fifties, I saw the graduating class of 400 pastors that year. And, you know, there were two or three like my dad. And I just was wondering, you know, What was that story like? What was it like to be there? So I walked down through the campus. I called up my mom when I got there, and I was like, “Mom, where did you all stay? What did you know?” She said, “Well, when we got married, we would stay down this block.” I walked down that block, and so it’s kind of nice to sort of live through his early life of being a pastor.

My father only being the youth pastor, and then after that when I was growing up, he couldn’t support the family as a youth pastor at a small church in Chinatown. And so what happened was he had to figure out, How am I going to feed the family? You know, my mother was home taking care of four kids. Daycare did not exist, if you will, in the way it does today. So he had to find other ways of living his life through his career the way he thought was the right way.

So he became a social worker, but was still very active in the church. So he had this sort of history with the church. They knew who he was. He was a former youth pastor. He grew up and everybody just knew everybody. But when he made the choice, I can’t take care of the family as a youth pastor, I’ll now become a social worker, what was that like for him, right? Did he feel like he failed, that he succeeded? What was most important, that he could still be a pastor, but without, if you will, the actual day to day process of being a pastor?

And I think that dynamic, which my mother helped him through, because she was the one that, of course, when he was putting together sermons in the old days, she was the brains behind the gig. And she would—my dad would write it in pencil on a yellow line pad of paper. She would then take it, edit it, type it. And I know that she encouraged him to do whatever was the right thing to do, but I never talked to him about it. But what I learned from that course of his decisions was that there are many ways of achieving what you would like to do without the official titles, without the official day to day.

So that existence was both watching in terms of the intersectionality, of his career, his faith, and then when his career changed, his faith did not. But then what he would always say is, you know, “Once a pastor, always a pastor, once a reverend, always a reverend—in everything you do.” You know, at the time I thought, You’re trying to make lemonade, I get it. But now, in my riper, older years, I really do think he’s right. I think he said it, because he is making lemonade, and we all have had to make lemonade. But I do believe you can carry it with you in so many different ways.

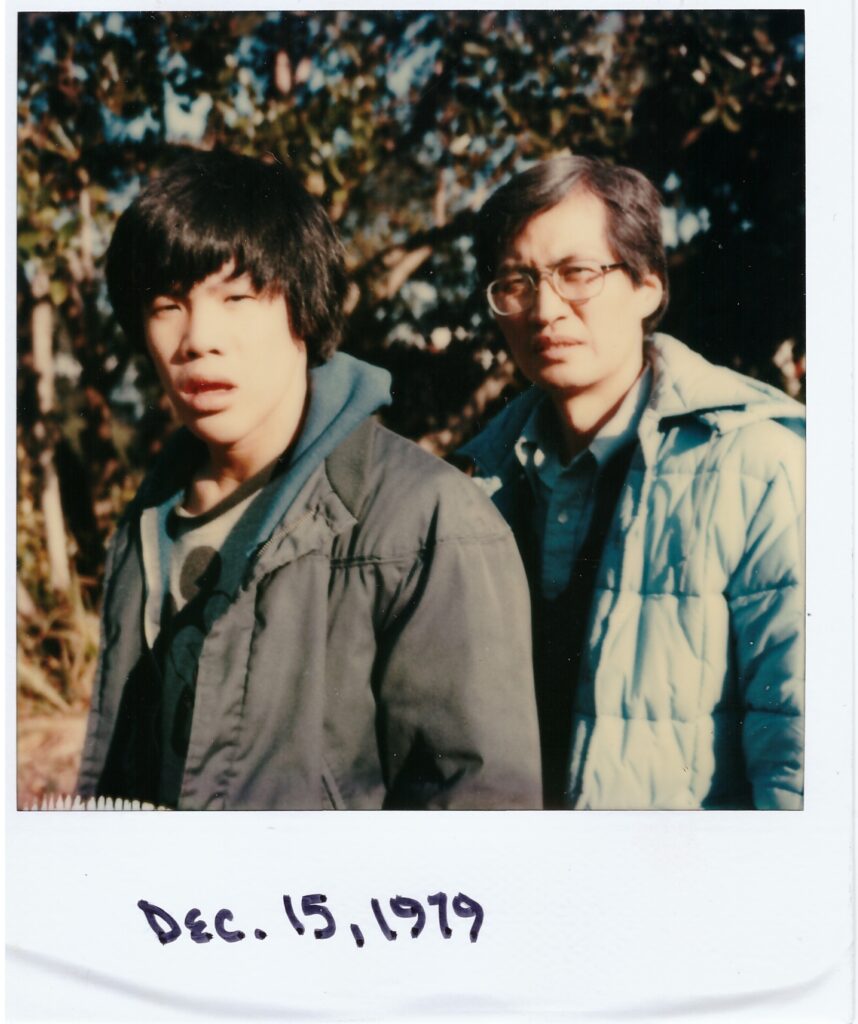

A Bumpy Road to Independence

I went through an issue as a high school student where I thought I was going to die. I had a small heart condition, and I figured it out when I was on the tennis court for the tennis team and I’d finally reached number three. And then I had a heart issue. So at the age of sixteen, I not only have the underlying I don’t like high school and now, because I won’t be here that long, I might as well not do what I don’t like very much. So I didn’t go to high school. I wouldn’t go to class. I got kicked out of one high school to another, almost did not graduate from the second high school. And you can just imagine the conversations in my household. But [my parents] were accepting, and I think they understood that this kid was going through this conversation that normally is not had until later in life.

And turns out, after much analysis, that it was benign, but for that month and a half, two months where they had no idea what it was, and to me as a high schooler, I didn’t know. So I didn’t go to college. And I worked at Mrs. Fields Cookies for four years. And so as I went through my career, you know, I started out in a very strange way in coming to journalism.

I finished business school at Michigan. And then after that, I didn’t go to work for the reason why I went to business school was to work in strategy consulting. Instead, you know, I ended up going to work in journalism. And I think what bit me at the time was sometimes you get up in the morning, and you walk outside and you take a deep breath and something hits your brain and hits you in a way that says, You know what, I think my calling just may have changed and what I want to do just changed. And it happened after investing all that time at business school.

“I think what bit me at the time was sometimes you get up in the morning, and you walk outside and you take a deep breath and something hits your brain and hits you in a way that says, You know what, I think my calling just may have changed and what I want to do just changed.” – Richard Lui

I ended up saying I couldn’t sell cookies for the rest of my life. I had learned a lot of great lessons at Mrs. Fields cookies, and I’m always going to be thankful for that. But then I went to City College of San Francisco and then transferred to a four-year university at Berkeley. And so when I was at Berkeley, I volunteered for the radio’s news station and some of the stories that I was able to report on as a cub reporter were stories like Rodney King and Magic Johnson getting HIV/AIDS and the first woman to be elected senator from my state. As a cub reporter, I was only there for two years. Right? And I think doing those stories left a big imprint on my brain about, Yeah, this stuff is important and we must tell these stories because there’s so much to be said about them and the honor and the obligation once you take on that story. I really took to heart, and I really gave it my all.

And I think along the way, what we learn is we have a way that we’d like to share, not necessarily my voice, or me being on camera, if you will. But I have a way or an understanding now of seeing things that need to be seen.

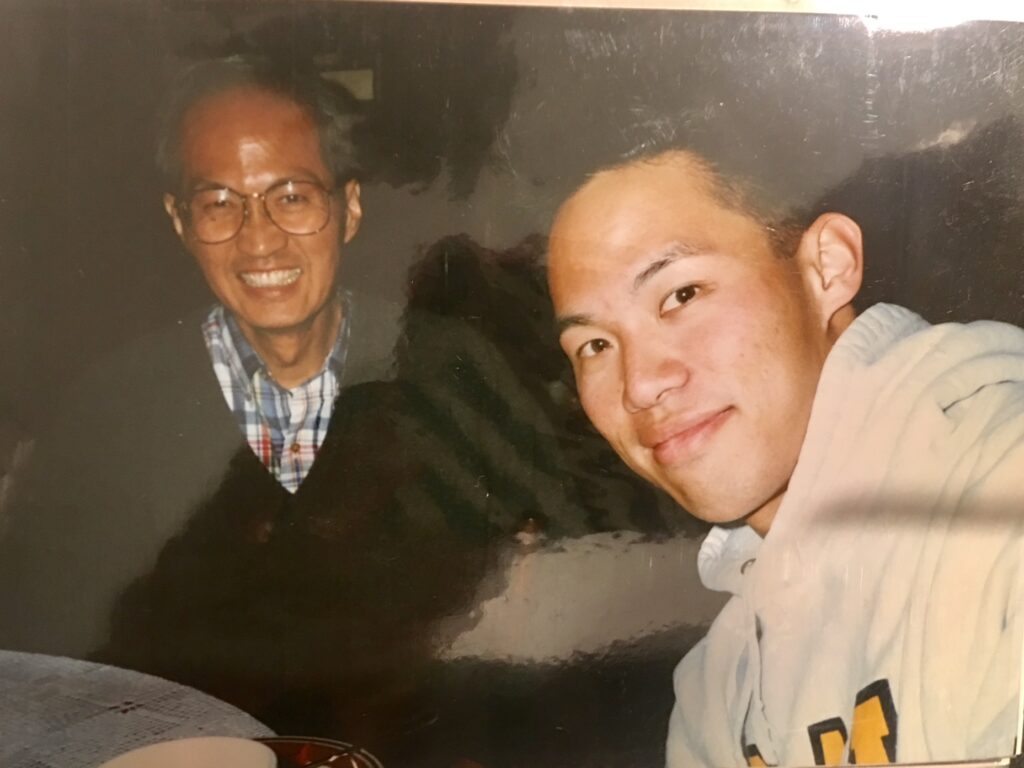

The Son Returns to the Father

Fifty-three million of us are family caregivers in America. Fifty-three million, and this measures from five years old, up to 110. And that’s a lot of us doing this stuff. But we’re not paid, we’re not trained. We do stuff sometimes that you don’t see in hospitals. We do things that sometimes you see every day, but mean more.

And for my father, during one of our Christmas gatherings—his sister—he came from a large family, thirteen siblings, and growing up poor, they knew each other really, really well. When they got together, it was like old home week when we’d get together six times a year. It was beautiful to see, you know what I mean?

And his youngest sister says, “Richard, you have some time?” during our pre-Christmas gathering. She said, “Your dad’s forgetting my name. Is everything okay, Richard?” I said, “Yeah, we knew that he might start doing that because he’s had discussions with a neurologist and I’ll have the talk with him to go to the next step to find out if he’s diagnosed with Alzheimer’s yet.”

And my dad, atypically male doing this, saying, “Okay, I’ll go in and check it.” So, you know, most folks like him would go, “No, what do you mean, I’m fine?” But he went and got checked. And yes, you do have Alzheimer’s, or the early stages. And so then began the journey of what did I want to do? Because we’ve, you know, looked and found out, did some research. And I said, “Well, he’s going to need help.” And what does that mean for me, working at 30 Rock in New York?

And so I walked into my boss’s office. So going straight in, I had a very straight approach with her, and I said, “I know you probably will have to let me go, because most journalists work eight days a week, twenty-five hours a day,” and I’m asking that I can’t do that. And she said, “Guess what, Richard? I’m a caregiver too, my mom’s in Florida. I’m up here. Let’s see what we can do together.” And then began my part-time job, and I started flying back and forth about three to five hundred thousand miles a year to take care of my dad.

And the thing I learned along the way—it was totally worth it, number one. Number two, he still had a lot to teach me without telling me.

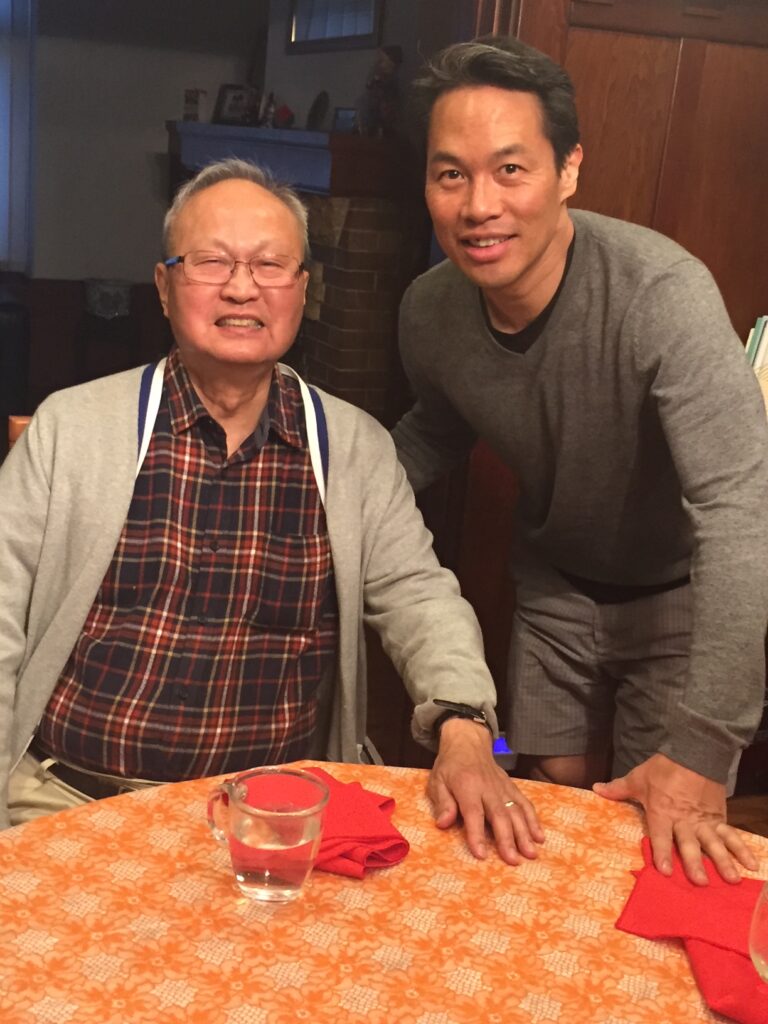

My father was not the negative reactor to the disease and there are many, sweetest, nicest, loving people—Alzheimer’s destroys that. It is an ugly disease. For my father, it reduced his stress. It took away his concern of, you know, I wanted to do more as a pastor, but I couldn’t dynamic. And so instead, he was a smiley, joyful person and would wave to everybody.

The one story I like to tell is that I’d come home for two or three days, three times a month, and I’d cook and do stuff. And I don’t cook, by the way, but I’d cook and I would do other stuff because Mom was working as the primary caregiver and my dad was running around like a twelve year old. Right? A ten year old. And just getting younger and younger. And so I’d be cooking and my dad, who loved to eat, because that’s what happens when Alzheimer’s increases in severity is that you just don’t know that you’re full. So you always want to eat and you start repeating things. So my dad will keep on going to want to take a shower. He’s the cleanest guy around, twenty showers a day.

So he saw me cutting food and said, “Ooh food.” But before he saw that, he wanted to take a shower. But we put a shut off valve. So he strips down, goes into the bathroom, which is right next to the kitchen, realizes that we had turned off the water. What he would do after that would walk outside naked and say, “Can you turn on the water for me?”

So he walks outside naked. Here he is, eighty-two year old man saying, “Can you turn on the water for me, Richard?” And I said, “No, you already took a shower.” Before I can even finish, “Ooh food, can I get some of that?” I said, “No, I’m not done yet.” And then he tried to grab it like a seven year old. And then what he would do after that—this is definitely a tactic children use all the time—he would hug me and say, “Oh, I love you. You’re so wonderful, Richard.” And there I was standing in the middle of my kitchen with a knife and cutting vegetables with a naked eighty-two year old Chinese American pastor smiling and laughing with me. And it’s one of the sweetest, nicest memories I have. It gave me a point of view that these little things I was doing, they were important, they’re important for my father, they were important for my mother, they’re important for my siblings, they’re important for the caregivers that would come over and take care of him.

“It gave me a point of view that these little things I was doing, they were important.” – Richard Lui, on caring for his father, who experienced Alzheimer’s Disease

It’s not only me that, as I think about self-care, my oldest brother—who you would not say would be the most selfless person, the most churchgoing person, the most easy to understand person—but one day he puts on the group chat, “So I was just there with Dad today at the care facility. I decided to read a chapter of the Bible to him.” And I was like, Who is this brother? What happened?

And he said, “Yeah, I read it to him,” in the group text, “I read it to him and he started to track, started to immediately come back to me.” And I was like, This makes complete sense. He named his two sons, my brother, after books of the Bible—and so was reading from John in this case. And we just started with John, started reading every chapter, every time we’d visit him. And there’s a lot of things as to why this was good, because it’s something that was very special to my father, his faith, his study, and also our voice. On top of that, maybe my dad really is smiling inside going, Ha ha, gotcha, because he got his oldest son to read a chapter of the Bible out loud. What an eye opener. What an eye opener.

Narrator: Richard closes his time with us by reading a passage from Jesus Calling that talks about gratefulness.

Richard: This is a passage from Jesus Calling, and the date is November 24th.

THANKFULNESS takes the sting out of adversity. That is why I’ve instructed you to give thanks for everything. There is an element of mystery in this transaction: You give Me thanks (regardless of your feelings), and I give you Joy (regardless of your circumstances). This is a spiritual act of obedience—at times, blind obedience. To people who don’t know Me intimately, it can seem irrational and even impossible to thank Me for heartrending hardships. Nonetheless, those who obey Me in this way are invariably blessed, even though difficulties may remain. Thankfulness opens your heart to My Presence and your mind to My thoughts. You may still be in the same place, with the same set of circumstances, but it is if a light has been switched on, enabling you to see from My perspective. It is the Light of My Presence that removes the sting from adversity.

Narrator: You can learn more about Richard’s story and his thoughts around pursuing a life of selflessness in his new book, Enough About Me: The Unexpected Power of Selflessness, available wherever books are sold.

If you’d like to hear more stories about being a man after God’s own heart, check out our interview with actor Greg Alan Williams.

Narrator: Next time on the Jesus Calling Podcast, we speak with author Charles Martin, who spent many years trying to figure out if he was meant to be a writer. The process was discouraging, and Charles found himself questioning if he was doing the right thing until one day, while reading the Bible, he began to understand that sometimes what seems illogical to us is totally logical to God.

Charles Martin: One day I found myself in Matthew 18. We read how the shepherd leaves the safety of the ninety-nine to chase down the one sheep who has again gotten himself lost and “gone astray”. So in God’s economy and in His kingdom, what is entirely illogical to us makes total sense to Him, which is the needs of the one outweigh that of the ninety-nine, and that regardless of what mess we may find ourselves in, regardless of the decisions we’ve made that have put us in a world of hurt, regardless of the stuff and just junk we litter our lives with, that each of us is worth rescue.