A Pilot & a POW Cling to Faith During Crisis: Tammie Jo Shults & Carlyle “Smitty” Harris

Tammie Jo: My definition of a hero is someone who takes the time to see, and the effort to act on behalf of someone else. It doesn’t require a title, no equipment, no superpowers—just attentive to someone besides yourself and willingness to act.

A Pilot & a POW Cling to Faith During Crisis: Tammie Jo Shults & Carlyle “Smitty” Harris – Episode #172

Narrator: Welcome to the Jesus Calling Podcast. Today we celebrate two heroes who not only courageously served in the United States military, but acted in true valor as they placed the lives of those they served above their own: Southwest Airlines pilot and retired Navy pilot, Captain Tammie Jo Shults, and retired Air Force pilot and former Vietnam POW, Colonel Carlyle “Smitty” Harris.

First up, in April 2018, Captain Shults was flying Southwest Flight #1380, when the left engine of the plane blew apart. She safely guided the plane down with one engine, and made a successful emergency landing. But before that day, Tammie Jo had spent years overcoming hurdles to achieve her dreams of being a pilot, and shares how one particular trial in her Navy years may have given her the training that helped her save 148 lives.

Capt. Tammie Jo Shults: I’m Tammie Jo Shults. I live here in Boerne, Texas. I’m a wife, and a mother, and am blessed to be in this time in history and in this country.

I also have had such an advantage in growing up in a wonderful home in New Mexico, [being] cherished by my family, and raised in a faith where there were no second-class citizens. So whenever I dreamed about what I wanted to do in life, I dreamed without fences.

“Whenever I dreamed about what I wanted to do in life, I dreamed without fences.” – Capt. Tammie Jo Shults

We did a lot of outdoor playing, I think, at the urging of my mom, even if we hadn’t wanted to. But we did. It was a lot of mud pies and pretending like we were pirates, or we were getting away from pirates, and it was pretty simple. And yet it was a wonderfully full childhood.

Our place was probably about thirty miles from Holloman Air Force Base, as the crow flies. They would practice air combat maneuvering, and they needed a ground reference point, so they used our big hay barn. That would be our daily air show while we were mucking out stalls or stocking trailers with organic fertilizer. I would see that and just think, That looks fantastic. I mean, not only cleaner than what I’m doing, but it just looks really exciting. But thinking about something and seeing it from a distance, never having met anyone who did that, it still seemed pretty out of reach.

And then I read a book called Jungle Pilot, which was about a Mission Aviation Fellowship pilot named Nate Saint. That was my eighth-grade summer, before I went into high school. And it just made me feel like I could see aviation from behind a pilot’s eyes. I felt like I got to wrap my mind around it, and that [becoming a pilot] was definitely what I wanted to do.

Refusing to believe that, “We don’t need girls.”

When I wrapped my mind around trying to get into flying, I realized that I’d like to do military flying, I’d like to serve my country. It was also a great way to learn to fly. I went to career day and the colonel at career day said, “Well, this is career day, not hobby day. You need to go find something girls can do.” And I was shocked because I had grown up in a family where there were no lines drawn between what I did and what my brother did. I was shocked that there were those lines in the real world, so to speak. After a few years at college, I saw a lady getting her Air Force wings at a winging. And so I went and talked to her, and she told me how she’d gotten in through ROTC. I was a junior, a senior in college, so it was too late for me to redo college in ROTC.

I went to the Air Force, which said, “No, you can’t take the test. We’re not giving you an application. We don’t need girls.” So I waited for a different recruiter to be behind the desk a few days later, and I went in and he said, “No, we don’t need girls.” So I went and cut out the advertisement in the newspaper, because they were advertising, “If you have your four-year degree and you want to fly, the Air Force wants you.” I cut it out and I went, and the Air Force recruiter said, “No. Don’t come back. If you have a brother, we’re interested. But we don’t need girls.” And the Army said, “You are not a fit for us.” And then the Navy said, “Sure, you can take a test.” It took them a couple of years before I could find a recruiter. It was about three recruiters later that I found one that would actually take my application. So yes, it took a while to get through that fortified line.

After getting my wings and going back to instruct for a couple of years for a great skipper, he had a change of command and I had a new skipper come on board. I was getting ready to teach the advanced stages in T-2s, like gunnery pattern and things like that. He pulled my gunnery pattern quall. I had done my test and everything to get ready to get my quall, and he said, “No. No girls are going to fly guns in my squadron.”

There weren’t girls, it was just me. But it was a very public shaming, and I was sent to teach out of control flight instead. It was one of those things where it wasn’t fair, but there are some times when we just have to take what’s not fair and work around it. I realized, You know, I’m assigned to fly out of control flight, so I will just do it the best I can.” And that actually was probably some of the best training I had in all my Navy experience, was my year of teaching out of control flight. I think part of that is learning not to be offended when you’re not treated fairly, but to reanalyze your own motives, your own merit.

“There are some times when we just have to take what’s not fair and and work around it.” – Capt. Tammie Jo Shults

My mom encouraged me on this. She said, “Take it to the Lord. Tell the Lord on them, and then pray for them, because it’s really hard to have the wrong attitude when you’ve laid it before the Lord. Then you pray for them.” That’s one of the reasons He asks us to pray for people that don’t treat us very well, because He’ll deal with them. But dealing with us, in our own heart, in that situation, is really the first step to overcoming it.

“He asks us to pray for people that don’t treat us very well, because He’ll deal with them. But dealing with us, in our own heart, in that situation, is really the first step to overcoming it.” – Capt. Tammie Jo Shults

Faith Produces Hope During Crisis

When I first got to Southwest, I realized that, I have more of a responsibility as an airline pilot than I did as an F-18 pilot. I have responsibilities for other people’s lives—not just flying the best aircraft I can, but how they’re treated onboard, too. That’s not just the flight attendants’ job. That’s the whole crew’s responsibility.

[On] April 17th last year, Darren Ellisor was my first officer, and we started in Nashville. We met the flight attendants—Rachel Fernheimer, Seanique Mallory, and Kathryn Sandoval—at the airplane for the first time. I try to make a habit of bringing coffee with me to the aircraft. It seems to bring everybody together faster than if I say, “You want to get together for the captain briefing?” So we all met around some coffee and chatted about the day ahead: how far we were all going and what the weather was like, different things like that. And then we had a little time to chat about where everybody was from and things like that. Kathryn had been at Southwest for six weeks on that day, so she was very new. And Seanique had come from being a customer service representative, I believe. Rachel [had been] flying for about four years for Southwest at the time.

When we landed at LaGuardia, we had a little extra time between flights. We got to chatting a little bit more, and realized a little bit more about each other before we took off. It was planned [to be] a four-hour flight. On Darren’s turn to fly, we took off, and twenty minutes into the flight, passing through thirty two thousand, five hundred feet.

Darren and I were comparing notes months after it happened, we both thought we’d been hit by another aircraft, the jolt was so hard.

We were pushed sideways, and the aircraft went into a snap roll to the left. We both lunged for the controls, and caught it going past forty degrees, the angle of bank, and righted it. By that time, we had initially seen the engines. The number one engine [was] rolling back, the instruments [were] blinking and showing that the engine had exploded, or wasn’t any good anymore. And then we couldn’t see anything, and we couldn’t hear anything, because after the initial shock of it all happening, we’re descending just because we’re heavy. We have this immense amount of drag now, where the engine had peeled back—something like a banana peeling—and remained attached. But now those big pieces were flailing in 500 miles an hour wind.

There was such a shudder involved with that, we couldn’t focus on the engine instrumentation. A cloud of smoke came in, probably from the exploded engine, through the air conditioning system. There was nothing to look at in the cockpit. I couldn’t focus on anything. I couldn’t communicate to anyone. There was a stabbing pain behind my ears, and I couldn’t breathe. It was kind of a forced moment of silence in that there was nothing I could really do. I remember looking out through the window, straight ahead, thinking, I’m not sure everything we need to fly is gonna stay on. I’ve never experienced anything quite like this. And if that’s the case, then this could be the day I meet my Maker.

You kind of have a mental rush doing this. Adrenaline kicks in, and you can think so leisurely, but in such a tiny slice of time. I remember getting to that mental cliff of, What if? And thinking, If that’s the case, and that’s when I stopped, and just stepped back and thought, I wouldn’t be meeting a stranger. And I had that calm that let me know that’s not really something I’m dreading.

But on the good side, the good news is that we were still flying, and I’m not sure everyone felt the same way about it that I did. The good news is we’re flying, we’ll just get back to work. And by that time, the smoke cleared out. We’d slowed down enough that we could see our engine instruments, read checklists, get our oxygen masks on, communicate a little bit. We’d told Philadelphia that we wanted to go to Philly, and then I communicated to the back, because I thought, As much as it’s startling for us appear in control of things and seeing what’s going on, it’s got to be mind-numbing fright going on in the back, where all you have is what’s happened. You have no knowledge of what’s going on.

I pushed my P.A. button and made a P.A. that said—it wasn’t my most elegant P.A.—”We’re not going down. We’re going into Philly.” Because I wanted them to know that the cockpit was still in control of the airplane. We had a plan, and we had a destination. And at that point, that’s when the flight attendants unbuckled and headed through an aisle that was so rough, they had sprained backs, bruised ribs, and lacerations just from going down the aisle to help people get their oxygen masks on and to tell them, “We’re going into Philly.”

It was a takeaway for me that that element of hope had such a change on people, and their actions, and their reactions. We didn’t change our circumstances. Hope doesn’t have to change our circumstances to change us.

“Hope doesn’t have to change our circumstances to change us.” – Capt. Tammie Jo Shults

The flight attendants unbuckled, started telling people what our destination was. And it wasn’t until they got even with row 14 that they saw where the breach in the cabin was and what had happened there. There were three passengers that unbuckled, left their oxygen masks and their families, to go towards an open, very dangerous window—not knowing if more would tear out. Tim McGinty, Andrew Needum, and then later Peggy Phillips, a retired nurse, unbuckled and came to do CPR on the passenger.

When we got closer to the ground, we had some issues to deal with that were new to us. The airplane, whenever I tried to add power and turn right, I wasn’t able to. I had so much drag pulling to the left. And when I added power, then that pushed us to the left. So there wasn’t any turning right until I did something differently.

There was just this pause in the cockpit voice recorder when we listened to it, and then you hear my voice just asking a question in two words and it’s, “Heavenly Father?” I didn’t realize until then that it was out loud. I thought it was a private conversation. But Darren kind of teased me, he goes, “I knew you were praying!” I said, “Yes, all the way down!”

But I was thinking, Heavenly Father, what am I missing? I know we didn’t wrestle with this for 30,000 feet not to be able to turn in the last two thousand and make it to the runway. And just kind of having that mental breathing room in prayer, I realized, Okay, asymmetrical thrust is pushing me away. So I took off the thrust, turned around, and then added a little bit back in. We weren’t able to add much thrust, because as we slowed down to land, that gave us less airflow over the rudder, which keeps our nose straight. So as I slowed down, I had less and less power available. I got our gear down at the right time so that we made the runway a little slower, and a little below glide slope, but we made the runway.

I was so impressed with the people onboard—not just the heroes that I mentioned, but also my crew, who were all amazing heroes in this situation. The entire group of passengers, when we landed, [didn’t have] angry frustration and [there wasn’t this] surge for the doors. I walked back to reassure people, help the flight attendants, and everyone was calmly seated, attentive to what we had to say. We told them, “We’d like for you to remain seated. There’s air stairs on the way, but we do have a medical emergency. We’d like to take care of her first, if you’ll remain seated.” Everyone was so attentive and quiet, and it just made me feel like everyone felt the value of human life that day. No one knew Jennifer, and Jennifer knew no one on that plane. But you don’t have to know someone for them to have value.

And of course, we were all glad that we had made the runway. But the survival of one hundred and forty-eight will never eclipse the loss of one. We were thrilled to return one hundred and forty-eight people to their lives and loved ones. It will always weigh heavy on our hearts that we weren’t able to do that for Jennifer. “There’s a time to weep and a time to laugh, a time to mourn and a time to dance.” I feel like that was the first day I understood those words.

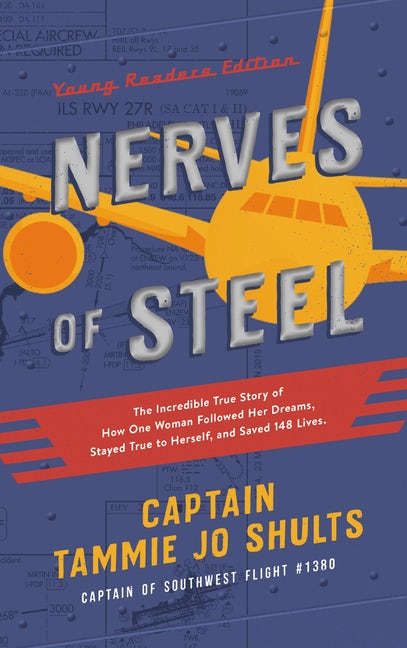

Narrator: Readers of all ages can learn about Tammie Jo’s new book Nerves of Steel, now available for adults and young readers. Listen now as Tammie reflects further on how God works in her life through prayer and devotion time, and as she reads a passage from Jesus Calling.

Tammie Jo: There are so many times that I’ve had incredible answers to prayer, or just witnessed some really cool things. Bible study time is sometimes separate from morning devotions, morning quiet time. For me, it is because I don’t always have the time in the morning to have a full-blown Bible study. But I need that one-on-one with the Lord before I face the day, before I face other people. Sarah [Young] has made that such a warm and engaging time with the Lord. August 17th:

Sometimes events whirl around you so quickly that they become a blur. Whisper My Name in recognition that I am still with you. Without skipping a beat in the activities that occupy you, you find strength and Peace through praying My Name. Later, when the happenings have run their course, you can talk with Me more fully. Accept each day just as it comes to you. Do not waste your time and energy wishing for a different set of circumstances. Instead, trust Me enough to yield to My design and purposes. Remember that nothing can separate you from My loving Presence; you are Mine.

Narrator: Stay tuned to hear the incredible story of Colonel Smitty Harris after a brief message about how you can start your Tuesday mornings in prayer with a community of believers during the Jesus Calling Weekly Prayer Call.

Did you know that Sarah Young, the author of Jesus Calling, prays for her readers each day? In that spirit, we want to extend the Jesus Calling prayer community out to you in a more personal way. Each Tuesday morning, you can dial in to the Jesus Calling Weekly Prayer Call, where the team from Jesus Calling and special guests will minister to us during a ten-minute call to reflect on that day’s passage from Jesus Calling, read scripture references, and pray together for each other and our world. Prayer call times are 8:00 a.m. Eastern, 7:00 a.m. Central, 6:00 a.m. Mountain, and 5:00 a.m. Pacific and are for U.S. only.

Did you know that Sarah Young, the author of Jesus Calling, prays for her readers each day? In that spirit, we want to extend the Jesus Calling prayer community out to you in a more personal way. Each Tuesday morning, you can dial in to the Jesus Calling Weekly Prayer Call, where the team from Jesus Calling and special guests will minister to us during a ten-minute call to reflect on that day’s passage from Jesus Calling, read scripture references, and pray together for each other and our world. Prayer call times are 8:00 a.m. Eastern, 7:00 a.m. Central, 6:00 a.m. Mountain, and 5:00 a.m. Pacific and are for U.S. only.

For more information on the Jesus Calling Weekly Prayer Call, or to submit prayer requests, please visit www.jesuscalling.com/prayer-call.

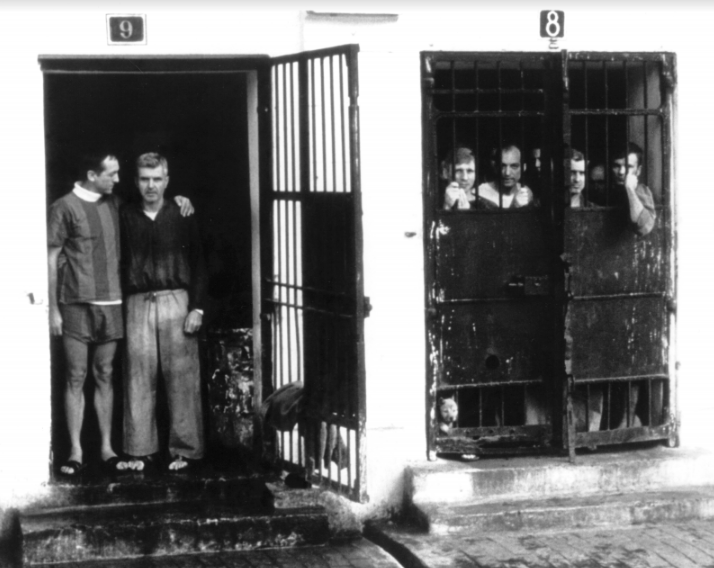

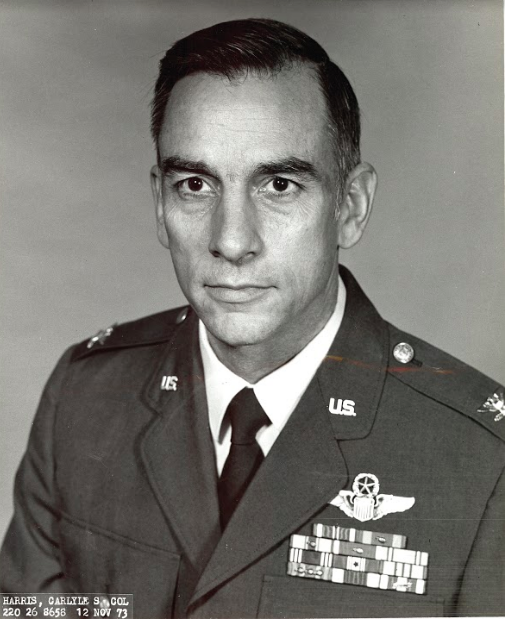

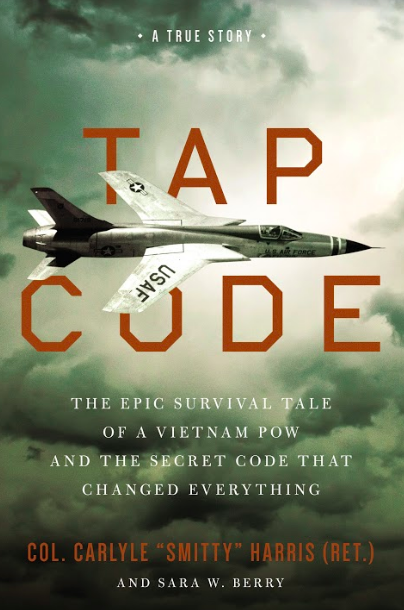

Narrator: When Air Force pilot Colonel Carlyle “Smitty” Harris was shot down over Vietnam on April 4th, 1965, he had no idea what horrors awaited him in the infamous “Hanoi Hilton” prison. For the next eight years, Smitty and hundreds of other American POWs suffered torture, solitary confinement, and abuse. But in the midst of the struggle, Smitty remembered learning the Tap Code—a World War II method of communication through tapping on a common water pipe. He covertly taught the code to many POWs, and the soldiers began to communicate about their shared love of God and country, which boosted morale as they endured their darkest days. Smitty begins his story by recalling the day he was shot down and captured.

Smitty: I had just dropped eight 750 pound bombs. And just as I bottomed out—we were going pretty close to the speed of sound, 600 miles an hour or so—some lucky gunner shot at me and the exploding round hit my engine area, which immediately knocked out my single engine aircraft, and I knew I was in trouble. I tried to restart the engine. There was so much happening at the moment. I really couldn’t think about anything, except I know I’m going to have to get out of this airplane.

I’d gone through the procedure many, many times in training. I pulled the trigger, [and it] worked perfectly, just as it had done in training. And the canopy went in about a half of a second later, the whole seat—with me in it—was shot up into the air, away from the airplane with my survival gear, including a dinghy. And of course, I was carrying a pistol and other survival equipment, a knife and whatnot. [It] all went out with me.

My idea was escape and evasion. So I looked around for hills or trees or ravines or anything where I could guide the parachute and maybe evade the enemy for a while, or maybe for good. But I looked down, and I was right above a large Vietnamese village. I was able to land just outside the village. I was met almost moments after I touched the ground. I knew I was going to be in North Vietnam, perhaps for a long time.

“I was right above a large Vietnamese village. I was able to land just outside the village. I was met almost moments after I touched the ground. I knew I was going to be in North Vietnam, perhaps for a long time.” – Col. Smitty Harris

The Tap Code Changes Everything

The North Vietnamese, they did a lot of things we didn’t understand. They pulled four of us out of solitary confinement and put us in a cell together. And later, a fifth joined us, Hayden Lockhart. I knew the tap code, and immediately said, “We’re going to have to communicate. Here is a way.” They all agreed. And not too long after that, several days, we were put back in solitary confinement, and we used the tap code successfully between us.

But as time went by, our communication became so fast and so good, and we were interested in so many things, between each other and trying to find out information. We found out all about the lives of the people around us, their kids, what they did, when they were shot down, what aircraft they flew or what carrier that they were on. Just a lot of information about each other, but we also found out a lot of our beliefs. We talked about God, religion, and how important it was, especially now. It turned out that we were all Christian.

“Our communication became so fast and so good, and we were interested in so many things, between each other and trying to find out information….We talked about God, religion, and how important it was, especially now. It turned out that we were all Christian.” – Col. Smitty Harris

We knew what day of the month it was, what day of the week. On Sunday, at first, one of us would thump the wall with our elbow, and it would matter that it could be heard throughout that area. And we knew we were going to observe some kind of Sunday service. I think most of us at that time, if we could kneel, would kneel and say the Lord’s Prayer and the Pledge of Allegiance and then whatever, [like] prayers. We wanted to continue for as long as we wanted to continue. That happened right off the bat.

In the last couple of years that we were there—well, from I think late ‘69 to when we were released. It was after the Son Tay raid, when they closed all the small camps. It was the best thing that ever happened to us. The North Vietnamese panicked, I think. In three days, all the little camps that usually had about fifty POWs were emptied, and we all came back to the big Hanoi Hilton, a big prison built by the French years ago. We were put in cells with about forty to fifty to a cell. Well, wasn’t that nice, to see friends and set up a chain of command.

We used our time productively. We had classes in almost anything you’d want. There would be someone in that group—it was pretty educated group, everyone had at least a Bachelor’s degree and [there were] quite a few Masters. Some had taught at the Air Force Academy and so on. In the time that I was at the Hanoi Hilton, in one of those cells, I learned three languages and could converse in German, Spanish, and French.

“We used our time productively. We had classes in almost anything you’d want. There would be someone in that group—it was pretty educated group, everyone had at least a Bachelor’s degree and [there were] quite a few Masters.” – Col. Smitty Harris

But there, on Sundays we could make a special thing of our church services. We knew that we could not make noises that could be heard outside our cell, or they [the Vietnamese] got very upset. We had a small choir who would sing quietly, and we would have someone who remembered scripture, and someone who would volunteer to give a little encouraging talk. We had a real church service.

It was essential, I think, to our emotional health. The feeling of community, and in being a part of something bigger than yourself, of praying together. We made a positive out of what they tried to [make] a negative, that is, solitary confinement and mistreatment.

Finding Links to Home

The hardest part about those eight years being away from my family was just that—being away from my family. I knew that Louise was soon to deliver our child after our a month after [I was] shot down and captured. And of course, we had two little girls that I adored. We were a very tight knit, loving family. I said prayers with the girls that night. I was a father. I helped discipline them when they needed it, but I don’t mean punished, because that was not necessary. They were good little girls. They knew that Mom and Dad were in charge.

“The hardest part about those eight years being away from my family was just that—being away from my family.” – Col. Smitty Harris

It was just a loving family, and those relationships I just missed so much. Particularly on special occasions, like a wedding anniversary and holidays, Easter, Christmas, I wondered how they were doing. I wondered a lot. I found out that Louise had had a son, our son Lyle. And I wondered what kind of little boy he would be and how he reacted with our daughters and so on. But it was just a total separation from all those family things that really made my life so meaningful before I was shot down.

When I got that first letter from Louise, I was really surprised because my cell [mate], Bob Shoemaker, and I had been brought to an interrogation room and interrogated together, which almost never happened. Of course, we got the usual propaganda effort by the interrogator and he asked us if we would like to receive a letter from home. Of course, we were overjoyed at the possibility.

He [the interrogator] singled out Shoe and said—I forget what they [the Vietnamese] called Shoe, but they usually used little short syllables. I was Ha. [The interrogator] handed him—Bob—this letter from his wife and dismissed him. And he said, “Ha! You do not get a letter because you have a bad attitude.” I was just stoic. I didn’t show emotion one way or the other. I expected bad things and I got bad things. But I did not react to them. I never reacted to the North Vietnamese over anything. Any emotion, or show of emotion, that I could control. Then I was released to go back to my cell.

Shoe showed me his letter, and he was very happy, and I was very happy for them. I think it was several days later, they [the Vietnamese] were getting ready to move us from that camp to somewhere else. I was called to interrogation and there was no usual propaganda or questions or anything. He just handed me a letter and dismissed me. It was my first letter from Louise and it was a picture of the [her] sitting back in a big easy chair with a drink in her hand. *Laughs*

I was so tickled and I cherished that letter, especially the picture.

Back on American Soil

After Ho Chi Minh died, there was a huge national mourning, and we knew that because there was a speaker in every cell. But when he died, we noticed quickly, probably within one to three months, that we weren’t mistreated as much. The torture—the really fierce, bad physical pressure—almost stopped. So things were better, and we were getting better food, a little more time outside. We heard over the loudspeakers that they were having peace talks in Paris, so we were pretty elated, and when they finally came in and pulled us all out and put us in trucks, we knew where we were going. [That was] the first time we had ever been moved with no blindfolds.

An escort officer, an American escort officer, that they brought in on the plane would turn us and we would march out to the airplane and get on. Never once showing the least bit of smile, even to the American officer, because the North Vietnamese were seeing everything we did, and we wanted to show how much we did not think of them. So we got on the airplane and we sat down quietly. And the ramp finally came up on that big C1-41 and it started taxiing out. We were quiet. We didn’t smile.

Shortly thereafter, during the climb out, we felt the big thump of the gear being retracted, and the whole plane erupted. We were yelling and screaming, jumping up, hugging each other, because we couldn’t before.

But I think one of the most moving times was when we finally landed in the Philippines, because we knew from our loudspeakers in our cells, we heard American voices talking about the anti-war movement in the United States and how our veterans had been treated. They came home, and many times they were spit at. They didn’t want to wear their uniforms, or people even to know they were veterans.

And so when we got off that airplane, we didn’t know what to expect. We walked down that ramp and look out. Whew. There were two or three thousand people waving banners. They had a huge about three or four foot tall banner stretched out [that said], “Welcome home.” We weren’t allowed to go out and mingle with them, but boy. That was our biggest emotion, relief, I think. We were back on American soil, [on an] American Air Force Base. [We had a] huge welcome and would soon be back with our families.

“Someone was always listening.”

Narrator: In celebration of veterans who have served in every branch of the military, Colonel Harris reads the November eleventh entry of Jesus Calling.

Smitty: Do not let any set of circumstances intimidate you. The more challenging your day, the more of My Power I place at your disposal. You seem to think that I empower you equally each day, but this is not so. Your tendency upon awakening is to assess the difficulties ahead of you, measuring them against your average strength. This is an exercise in unreality. I know what each of your days will contain, and I empower you accordingly. The degree to which I strengthen you on a given day is based mainly on two variables: the difficulty of your circumstances, and your willingness to depend on Me for help. Try to view challenging days as opportunities to receive more of My Power than usual. Look to Me for all that you need, and watch to see what I will do. As your day, so shall your strength be.

That is so on—hitting the nail on the head for me. After Vietnam, I think my outlook is different. I used to, during my eight years [in Vietnam], I developed a communication with God. And I knew, even in the darkest times, when things were at their lowest, lowest ebb, I knew I could always pray and I knew someone was listening who could do something about it. He was there for me.

“And I knew, even in the darkest times, when things were at their lowest, lowest ebb, I knew I could always pray and I knew someone was listening who could do something about it.” – Col. Carlyle “Smitty” Harris

Narrator: You can learn more about Smitty’s story, including the story of his wife Louise as she cared for their family back home, in the new book Tap Code, available from your favorite book retailer today.

(Editor’s note: The first chapter of Tap Code is available to listen on audiobook.)

Narrator: If you’d like to hear more stories about veterans and heroes, check out our interview with Chick-fil-A Foundation executive and retired military serviceman Rodney D. Bullard.

Narrator: Next time on the Jesus Calling Podcast, we talk with author Sally Clarkson and her son Nathan Clarkson. As a child, Nathan noticed that he learned and processed his emotions differently from the other kids around him, which made him feel isolated. But with his mother’s support and God’s love, he learned that his differences could actually be used for good.

Nathan Clarkson: You know, the thing about feeling different and realizing your difference, especially as young kids, it can make you feel very alone, and it can make you feel very different, and sometimes it can just make you feel bad or broken because you don’t work like the rest of the world. It was an interesting thing to feel all these things and then look at the God from the Bible, and He’s one of peace and love. As I started digging in, even in the midst of my adolescent angst, I found a God who says He loved me as I was, and I found a God who said I was made for purpose and that all these differences could be used for His glory and for the story that He wanted to tell with my life.

Narrator: Do you love hearing these stories of faith weekly from people like you whose lives have been changed by a closer walk with God? Then be sure to subscribe to the Jesus Calling: Stories of Faith Podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever you listen to your podcasts. If you like what you’re hearing, leave us a review so that we can reach others with these inspirational stories. And, you can also see these interviews on video as part of our original web series with a new interview premiering every other Sunday on Facebook Live. Find previously broadcasted interviews on our Youtube channel, on IGTV, or on www.jesuscalling.com/media/video.

One thought on “A Pilot & a POW Cling to Faith During Crisis: Tammie Jo Shults & Carlyle “Smitty” Harris”

Comments are closed.